Guest post by Arizona Humanities speaker Elsie Szecsy

How do we know when a historical account is complete? When do we know that we have enough information to draw accurate conclusions about how something from the past came to be, how it operated, why it ended, and its after-effects? What happens when different historical accounts seem to contradict each other? In the three years that I have been researching the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps, these questions have arisen repeatedly.

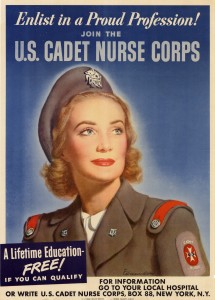

The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps was an emergency program that addressed a critical shortage of nurses in stateside hospitals during World War II. In exchange for a promise to serve in essential nursing service for the duration of the War, Cadet Nurses received a free nursing education.

Almost a decade before the Civil Rights movement began to gain traction in the 1950s, the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps included a non-discrimination clause. Schools of nursing participating in the program would not be permitted to discriminate on the basis of race or ethnicity. That discriminatory practices in nursing education prevailed before World War II is probably no surprise. That these practices were being challenged before the 1950s might be.

In light of the recently televised Ken Burns documentary, The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, one can begin to understand a political context for the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps with roots in the Great Depression. Through the examination of curriculum developmental processes that began as early as World War I, one can see a trajectory to professionalize nursing and improve nurse education. Taking both into account in Arizona, one can appreciate an incredibly rich story that includes Sage Memorial, the nation’s only accredited and highly successful school of nursing for Native Americans in Ganado, Arizona, and Santa Monica’s, the nation’s first inter-racial hospital and school of nursing west of the Mississippi River in Phoenix. One can also begin to see the Corps’ effects in Arizona after the war through Cadet Nurses’ presence in building nursing programs at the university and community college, in other health initiatives with Native Americans, and in school nursing in Arizona.

Nonetheless, other questions arise. Was the required high school education for admission into the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps equally accessible to all women in Arizona? Also, to what degree were African Americans, Latinas, and Native Americans permitted to draw from their heritage in becoming a nurse in Arizona?

Did the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps’ non-discrimination clause make a difference? Did it help promote equitable opportunity and access to high quality nurse education in Arizona during World War II? It is hard to tell, but it did not appear to hurt. This investigation is a work-in-progress, and it might become more complete over time through documentation of the thoughts of Cadet Nurses in Arizona and elsewhere in the United States. Though I may be resigned to the possibility that we may never know the whole story, this possibility does not dissuade me from persevering in this research.

Click here to read more about the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps.

You can invite Elsie to to speak at your organization or school through the AZ Speaks program.

Elsie Szecsy holds an Ed.D. in educational administration from Teachers College, Columbia University in New York City. She is an academic professional and qualitative research methodologist at Arizona State University in Tempe. Her research on the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps employs social historical methods, where she studies the past as looking up from rather than back or down to the past. This method elicits views of events through the lens of those who experienced them. In 2014 she talked about the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps at a Nurse Recognition Day Conference hosted by the U.S. Public Health Service in Bethesda, Maryland, and at the annual conference of the American Association for the History of Nursing in Hartford, Connecticut.

Elsie Szecsy holds an Ed.D. in educational administration from Teachers College, Columbia University in New York City. She is an academic professional and qualitative research methodologist at Arizona State University in Tempe. Her research on the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps employs social historical methods, where she studies the past as looking up from rather than back or down to the past. This method elicits views of events through the lens of those who experienced them. In 2014 she talked about the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps at a Nurse Recognition Day Conference hosted by the U.S. Public Health Service in Bethesda, Maryland, and at the annual conference of the American Association for the History of Nursing in Hartford, Connecticut.